When You're Strange . . .

When my sister and I were young, the highlight of our summer was when we would journey "down south" to visit our relatives. Our days were full of picnics and family reunions, watermelons and beans straight off the vine, berries with pricklers and tiny red chiggers that burrowed under our skin, swamp explorations and tiny baby turtles that snapped at our fingers when we tried to rescue them from oncoming cars. Our nights were full of revival meetings, family bruhahas, grown up dramas that we didn't quite understand, and enough haints and spooks to last a lifetime. In spite of the rather considerable monotony of being in a small, rural town, for us it was like a fairy tale land full of never-ending discoveries. Still, we never quite fit in, and by the end of the summer, we were eager to return home. It was on one of the picnic days while we were at some kind of reunion or gathering for church or family folk too numerous to remember that a little boy approached us, the "northern cousins." After noticing that he was standing and staring, mouth agape, we attempted to do the polite thing and engage him in conversation about the weather or horseshoes or maybe even the abundant barbeque offerings. He said nothing. So, we turned back to our own little circle, my older cousins intent in their discussion of cute boys, my sister trying to mimic them, and I lost in my musings, when suddenly the boy blurted out, "Yew Tawooooook Faweeny." All conversation ceased and then, as one, we burst into torrents of laughter at the absurdity of being told that we talk funny by someone we could barely understand. Even now, thirty odd years later, we still chuckle about that moment. Certainly, we understood then as we do now that that moment was the consequence of two cultures colliding on a very small scale; however, it is illustrative of clashing cultures on a larger scale.

My son has a friend of proximity who delights in telling him that he's "weird." Yesterday, both boys were at a birthday party, and my son was being his usual loud, charming, engaging self -- meaning he was doing some seriously over-the-top acting about some scenario in which life as we know it was being imperiled by something trivial (it's a teen thing). The other teens were looking on with a kind of amused fascination (my son's usual effect on his peers) when the friend declared repeatedly that my son is weird. Failing to get the anticipated chorus of agreement, the child continued to escalate, shouting about my son's weirdness until someone politely changed the subject. Now, this other child couldn't find "normal" if he was standing on a path right outside of it with a huge sign pointing the way. Still, he felt it incumbent upon himself to attempt to control my son's behavior through social censure because joie de vivre made him feel uncomfortable.

Shortly after publishing this blog I received a subtle (or not -- frankly, anything less than direct communication is wasted on me) comment about homeschoolers in general and me specifically sneering at education. Since I spend almost every day of the year engaged in the education of my own children, and promoting the education and care of other people's children, my first response was to laugh out loud. However, since the comment was made by a person who has taken a rather unconventional path in life herself, I began to think about exactly what it is that drives people to move from a recognition of difference to a desire to repress that difference -- from noticing that someone "talks funny" to trying to silence them in the interest of cultural hegemony.

Every parent, at some point, has received unwelcome and generally asinine advice about parenting from a childless friend who suddenly considers him or herself to be the new Dr. Sears. Generally, we parents grit our teeth, murmur politely, or roll our eyes discretely to allow these people to remain secure in their cocoon of self-importance. Fortunately, those people are no real threat to our parenthood. In the case of homeschool, however, the uninformed, particularly when they are responsible for educational policy, can be quite dangerous. In an era in which we are aware that patently wrong ideas exist in the minds of those in power like only "legitimate rape" can lead to pregnancy and same sex marriage leads to bestiality; in an era of wrong-headed school policies in which six year olds are arrested for sexual harassment for singing the lyrics to a popular song or 9 year olds are arrested and expelled for performing science experiments, homeschoolers are right to be concerned about misconceptions and outright prejudice depriving us of our right to raise and educate our children in the manner that we see fit.

The complication in identifying prejudice and repression is that it often can appear quite benign. I have had people ask me, while my kids were at soccer, swimming, football, art classes, the playground or other activities with their kids, how my poor deprived children would ever be "socialized" or have the opportunity to be friends with other children. It is as though the evidence of their own eyes is insufficient to refute their wrong assumptions. I have listened to parents wax eloquent about the many ways in which their children are being failed by the system, only to have them berate me for abandoning traditional education to create a curriculum tailored to my children's learning styles and interests. I have had teachers complain about being underfunded, overworked, and under-appreciated within their schools, and then heap vitriol upon my head as though my choice to not add to their burden is somehow responsible for the decline of civilization. There is always that moment, that transformation, where there is a recognition that what I am doing is different that leads to condescension, anger, fear and disapproval -- a response designed to return a penitent me to the fold. So, back to the central question at hand: What drives this need for conformity and sameness?

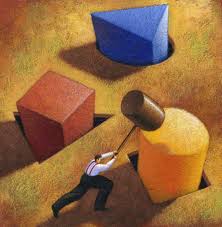

The school system as we know it was one of the by-products of the industrial revolution. Cheap child laborers were taking jobs from adults and, as they matured, these poorly educated new adults lacked both the desired temperament and the skill set to become the workers that industry demanded. Enter institutionalized education. Based on a factory model, children were segregated by age and taught the skills that they would need to be obedient cogs in the machine.More than subject matter, what schools teach is the importance of conformity. Few people remember the content of the lessons they learned as children, but all remember the attitude. And, unfortunately, it is this blind acceptance of the "naturalness" of artifice that renders us complicit in the failure of our educational system to produce wisdom, creativity and vision in the majority of its graduates. What if, however, we embraced another model for education? What if we were willing to set aside our fears of difference, of weirdness, of talking or thinking funny, and we focused on children and determined the best way to grow human beings capable of the kind of thought necessary for a technological age?

Many people cite Thomas Edison as evidence that a quirky, somewhat homeschooled child can grow up and make good; however, to me, what is most important about Edison is not that he can be claimed within the tribe, but that his idea factory provides an alternative factory model that we can look to when discussing models for education. Because, in my mind, Edison's greatest invention, his greatest legacy, was instilling in popular culture an understanding that curiosity, experimentation, failure, passion -- the production and improvement of ideas -- is what leads to progress, not simply accepting the status quo. Edison's incandescent lamp was not a new idea; it was a better idea. And, fortunately for us, no one accused him of sneering at the inherent "rightness" of God-given darkness when he developed it.

My son has a friend of proximity who delights in telling him that he's "weird." Yesterday, both boys were at a birthday party, and my son was being his usual loud, charming, engaging self -- meaning he was doing some seriously over-the-top acting about some scenario in which life as we know it was being imperiled by something trivial (it's a teen thing). The other teens were looking on with a kind of amused fascination (my son's usual effect on his peers) when the friend declared repeatedly that my son is weird. Failing to get the anticipated chorus of agreement, the child continued to escalate, shouting about my son's weirdness until someone politely changed the subject. Now, this other child couldn't find "normal" if he was standing on a path right outside of it with a huge sign pointing the way. Still, he felt it incumbent upon himself to attempt to control my son's behavior through social censure because joie de vivre made him feel uncomfortable.

Shortly after publishing this blog I received a subtle (or not -- frankly, anything less than direct communication is wasted on me) comment about homeschoolers in general and me specifically sneering at education. Since I spend almost every day of the year engaged in the education of my own children, and promoting the education and care of other people's children, my first response was to laugh out loud. However, since the comment was made by a person who has taken a rather unconventional path in life herself, I began to think about exactly what it is that drives people to move from a recognition of difference to a desire to repress that difference -- from noticing that someone "talks funny" to trying to silence them in the interest of cultural hegemony.

Every parent, at some point, has received unwelcome and generally asinine advice about parenting from a childless friend who suddenly considers him or herself to be the new Dr. Sears. Generally, we parents grit our teeth, murmur politely, or roll our eyes discretely to allow these people to remain secure in their cocoon of self-importance. Fortunately, those people are no real threat to our parenthood. In the case of homeschool, however, the uninformed, particularly when they are responsible for educational policy, can be quite dangerous. In an era in which we are aware that patently wrong ideas exist in the minds of those in power like only "legitimate rape" can lead to pregnancy and same sex marriage leads to bestiality; in an era of wrong-headed school policies in which six year olds are arrested for sexual harassment for singing the lyrics to a popular song or 9 year olds are arrested and expelled for performing science experiments, homeschoolers are right to be concerned about misconceptions and outright prejudice depriving us of our right to raise and educate our children in the manner that we see fit.

The complication in identifying prejudice and repression is that it often can appear quite benign. I have had people ask me, while my kids were at soccer, swimming, football, art classes, the playground or other activities with their kids, how my poor deprived children would ever be "socialized" or have the opportunity to be friends with other children. It is as though the evidence of their own eyes is insufficient to refute their wrong assumptions. I have listened to parents wax eloquent about the many ways in which their children are being failed by the system, only to have them berate me for abandoning traditional education to create a curriculum tailored to my children's learning styles and interests. I have had teachers complain about being underfunded, overworked, and under-appreciated within their schools, and then heap vitriol upon my head as though my choice to not add to their burden is somehow responsible for the decline of civilization. There is always that moment, that transformation, where there is a recognition that what I am doing is different that leads to condescension, anger, fear and disapproval -- a response designed to return a penitent me to the fold. So, back to the central question at hand: What drives this need for conformity and sameness?

The school system as we know it was one of the by-products of the industrial revolution. Cheap child laborers were taking jobs from adults and, as they matured, these poorly educated new adults lacked both the desired temperament and the skill set to become the workers that industry demanded. Enter institutionalized education. Based on a factory model, children were segregated by age and taught the skills that they would need to be obedient cogs in the machine.More than subject matter, what schools teach is the importance of conformity. Few people remember the content of the lessons they learned as children, but all remember the attitude. And, unfortunately, it is this blind acceptance of the "naturalness" of artifice that renders us complicit in the failure of our educational system to produce wisdom, creativity and vision in the majority of its graduates. What if, however, we embraced another model for education? What if we were willing to set aside our fears of difference, of weirdness, of talking or thinking funny, and we focused on children and determined the best way to grow human beings capable of the kind of thought necessary for a technological age?

Many people cite Thomas Edison as evidence that a quirky, somewhat homeschooled child can grow up and make good; however, to me, what is most important about Edison is not that he can be claimed within the tribe, but that his idea factory provides an alternative factory model that we can look to when discussing models for education. Because, in my mind, Edison's greatest invention, his greatest legacy, was instilling in popular culture an understanding that curiosity, experimentation, failure, passion -- the production and improvement of ideas -- is what leads to progress, not simply accepting the status quo. Edison's incandescent lamp was not a new idea; it was a better idea. And, fortunately for us, no one accused him of sneering at the inherent "rightness" of God-given darkness when he developed it.